Brainwashing

In 1994, Jean-Claude, a Hutu policeman later turned «Tutsi hunter,» was 26 years old and one of 14 police officers in the commune of Nyamata, an hour outside Kigali, one of the areas worst affected by the genocide.

Four years earlier, the Rwandan Patriotic Front had attacked Rwanda from Uganda. The movement was made up of mainly Tutsis, living in exile since 1959, whom the Rwandan regime had not wanted to let return to the country.

In 1990, after that attack, Jean-Claude and his colleagues, on the orders of the authorities, began harassing the Tutsis in the commune, arresting them for no reason and beating them up. In 1992, dozens were killed and their homes burnt down…. Until 1994, during meetings, the authorities had kept repeating that the Tutsis were «snakes» and «cockroaches,» and that the Rwandan Patriotic Front would, according to their truncated vision of history, «bring back serfdom» (of the Hutus by the Tutsis), a powerful theme in the imagination of the regime.

The Rwandans were fed the message that the Tutsis, all the Tutsis, who had been second-class citizens since 1959, were allies of the exiled group that had attacked them. When Rwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana’s plane was shot down on the evening of April 6, the authorities were quick to spread an accusatory discourse: «Here is the proof that what we told you was true, they killed our President.»

«I shoot in the bush like the others»

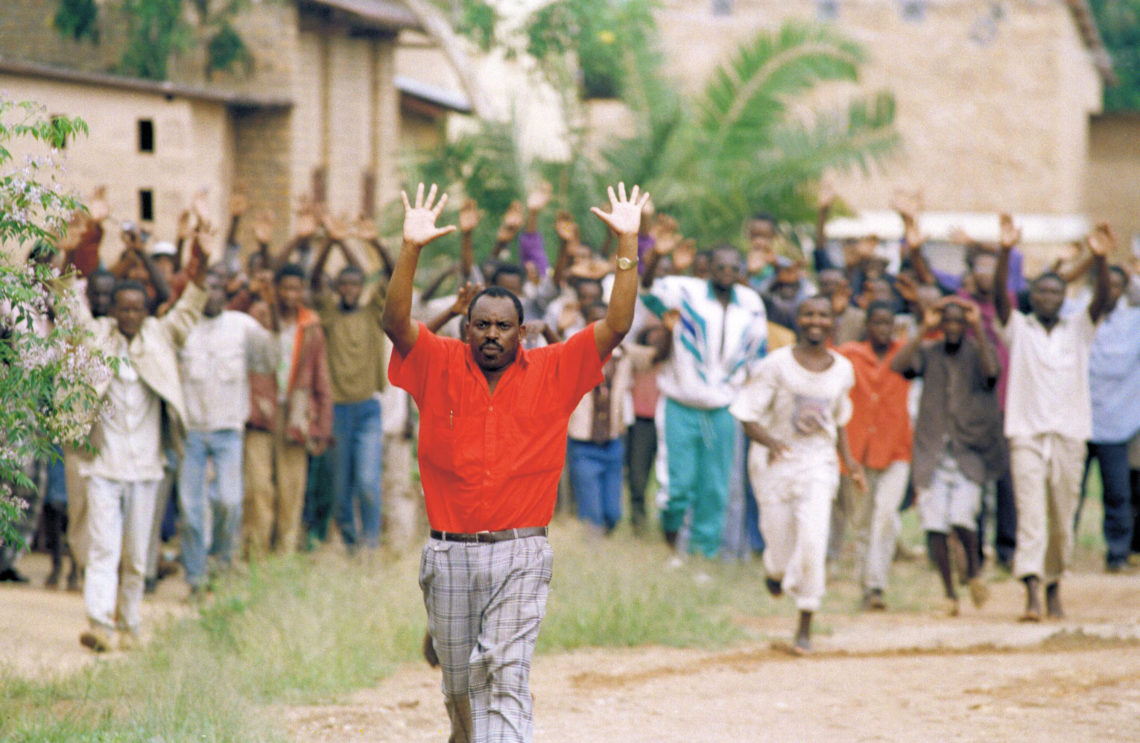

On the evening of April 10, when soldiers arrived in Rwanda, the police showed them the houses of the Tutsis in order to kill them. Many of them had taken refuge in the local church, and others in a plot of land opposite the communal house, where there were several thousand frightened people, thinking that the authorities were going to protect them. Instead, the authorities conveniently decided to kill them on the spot. The soldiers and police, armed with rifles and grenades, and the militiamen with machetes and spiked clubs, surrounded the refugees and began firing into the crowd, throwing grenades and machetes.

Jean-Claude starts shooting at those closest to him, then, as the defenceless victims fall, towards the center of the crowd. He shoots and shoots and shoots some more. He had ten cartridges for his single-shot rifle and, when he ran out, he was supplied with new ones. The militiamen finish the job with machetes and clubs. It was a veritable carnage, a butchery, a massacre. How many people did he kill? He doesn’t know, or refuses to say. He fired into the crowd like the others.

What is certain is that he killed every day for a month, first in the center of the village, then later in the forests and marshes, and that he never ran out of ammunition. How did he feel? «At first it was fear,» he tells us, «but then the fear disappeared, there was no joy either, it became a habit to kill. It was a job ordered by the authorities and we did our duty.» He took orders and obeyed, like Adolf Eichmann and the other Nazi executioners of the Final Solution…. [T]he Hutu killers showed neither guilt nor remorse. Their confessions were mechanical, made in obedience to the new authorities. But deep down, no trace of guilt feelings emerges.

From the forthcoming book, Rwanda 94 le Carnage: 30 ans après, retour sur place (Rwanda ’94, the Carnage: 30 Years After, A Return To the Site)

Alain Destexhe was Secretary General of Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) in 1994 during the genocide. He has also published Rwanda and Genocide in the Twentieth Century, New York University Press, 1995